Desdemona: who is she? Who is this young and rebellious woman escaping her father and tearing apart all conventional roles of her time? Is she perhaps representing all of us? Not so. For this exhibition in fact, we are asking Desdemona to represent every single woman that has been murdered.

Only for one night, for love, Desdemona eludes the rules. From that moment onwards, all the male characters in the Shakespearean play, will describe her as a dangerous creature: “Look to her, Moor, if thou hast eyes to see. She has deceived her father, and may thee” tells Brabantio to Othello, who apparently is not listening, but never will forget that first description of her loved one, just as we will never forget it either. At the same time Iago as soon as he appears on the scene describes her in a way to say the least pornographic.

Harold Bloom is right when he writes that Shakespeare does not reproduce nature, he invents man and all that is most frightening about him: “Under certain aspects, Othello is the most offensive Shakespearean representation of masculine vanity and of feminine sexual fear, the masculine equation: blending into a single preoccupation both fear of betrayal and mortality.”

Hence, Desdemona is that creature which not only represents the silent victim, but she is also the one who decides, the one who starts a relationship of reciprocal seduction and whose decisions as such are described from men as a betrayal.

Please no, not Desdemona, not any other murdered woman is a victim beforehand. She only becomes a victim inside a tragic and offensive unbalanced relationship.

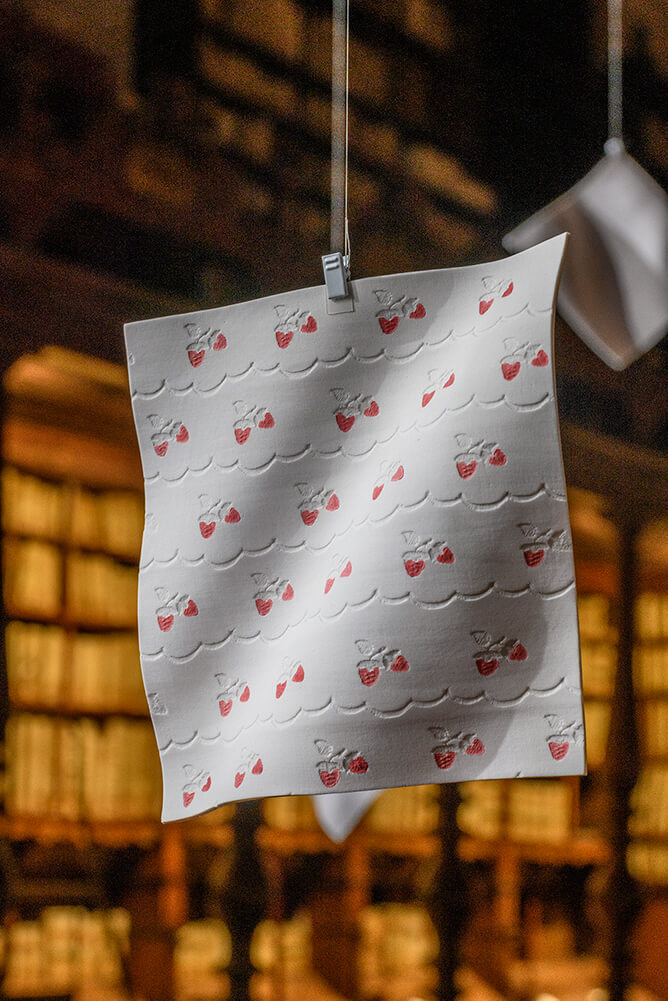

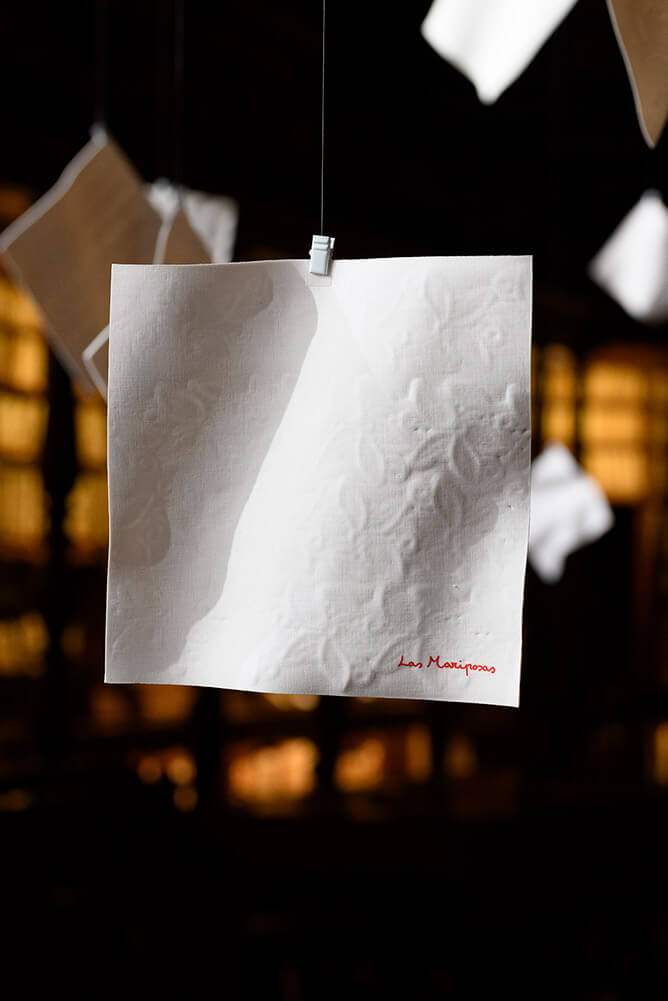

Within that handkerchief, also described by as a “miserable wedding present” by Shakespearean contemporaries, we find the young woman, their relationship, and Othello’s past, we also discover a masculine dominion with all those characters living around the relationship. In fact that seemingly silent object mutates during the tragic unfolding of the text: it’s a napkin in the beginning, it later becomes a handkerchief, and eventually will deteriorate into a trifle. We are witnessing the denial of a whole life.

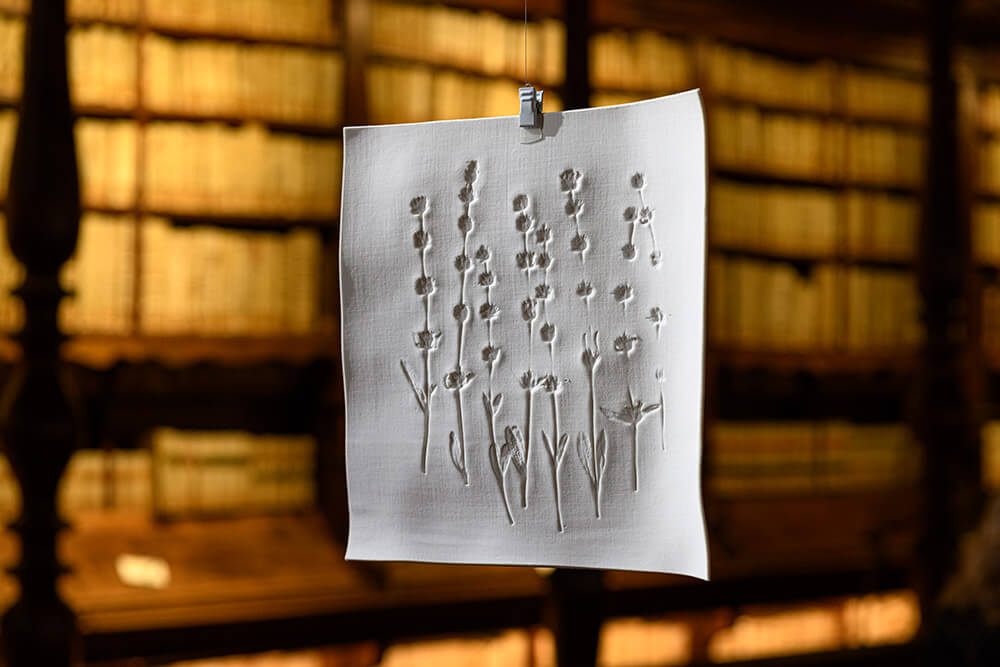

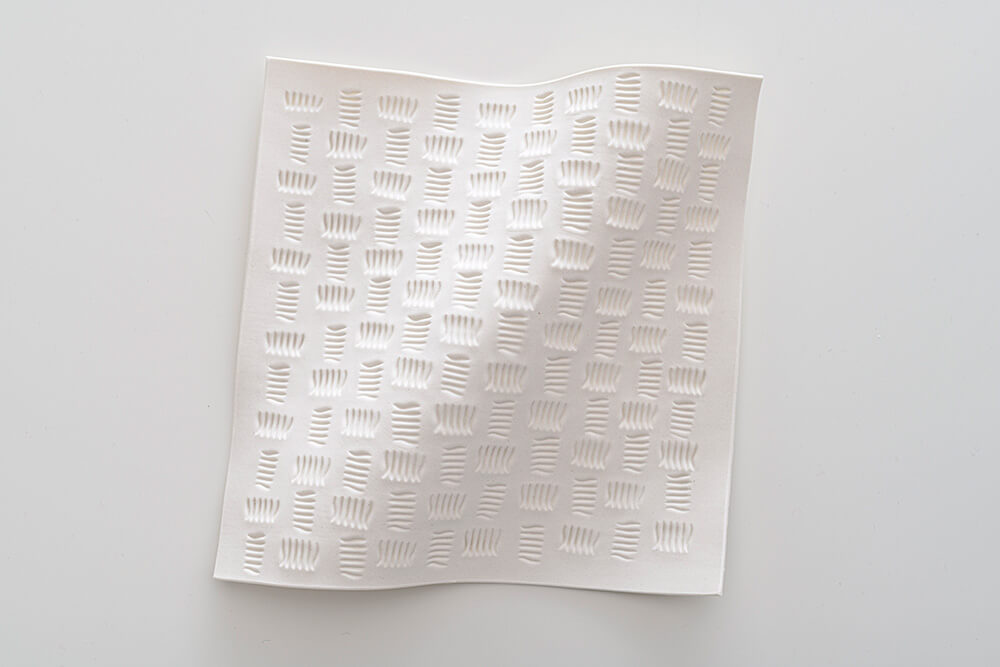

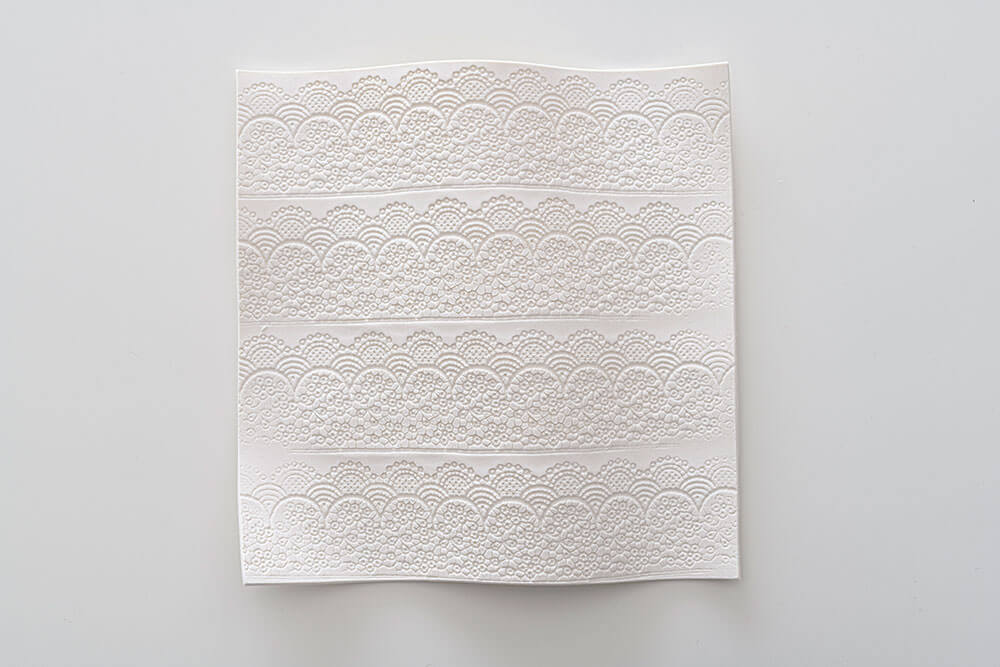

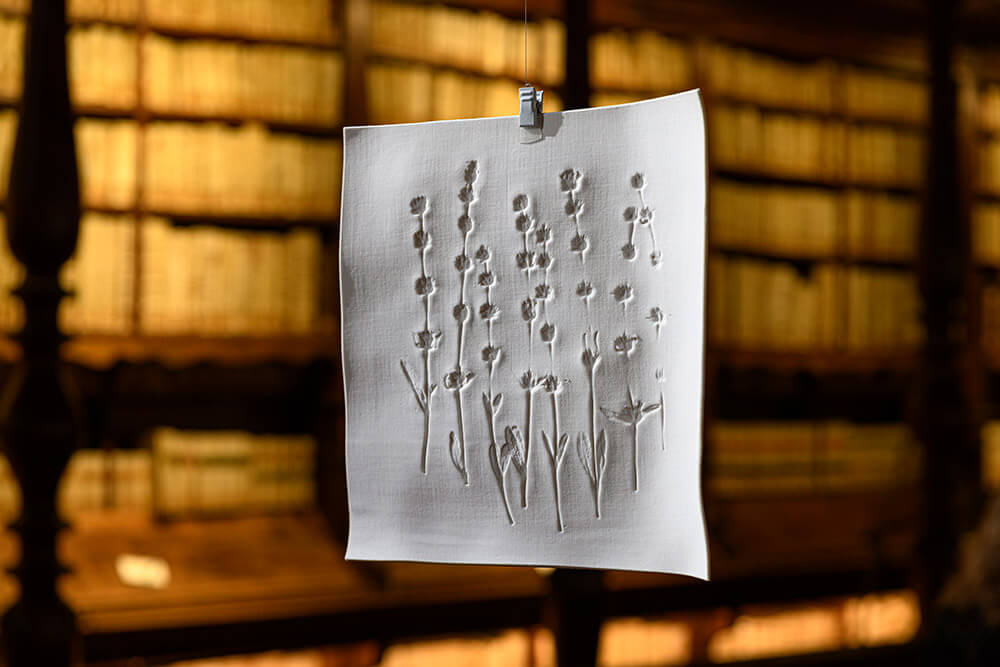

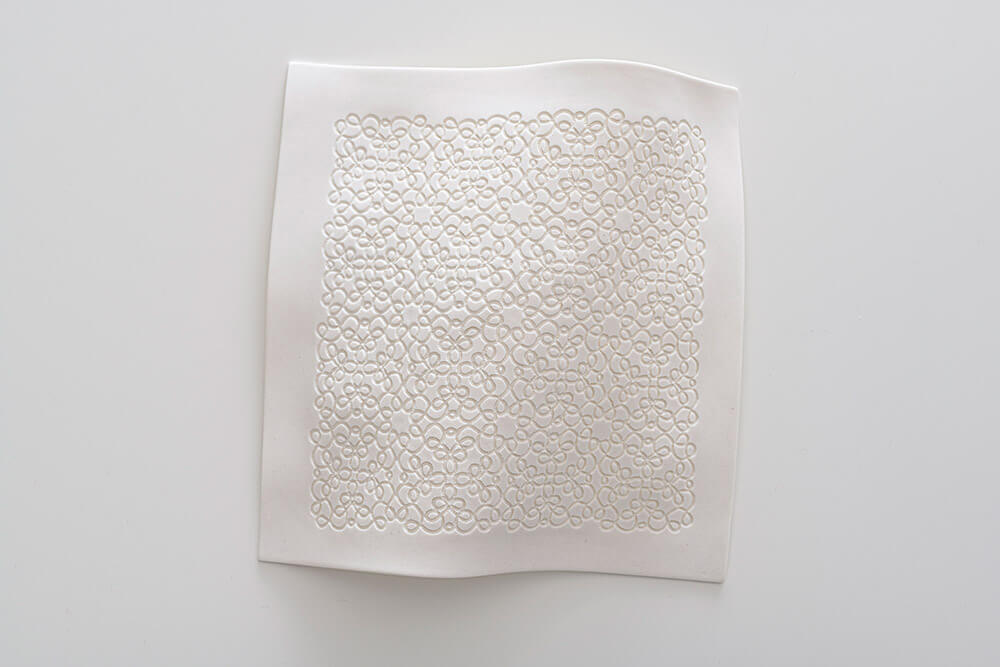

This is where Emanuela Mastria begins: that simple handkerchief, deprived of senses, empty of a past or history except for a miserable useless and hurtful murmur, all contrives into the density of a life, of unbearable emotions, of hopelessness, violence, and unthinkable actions.

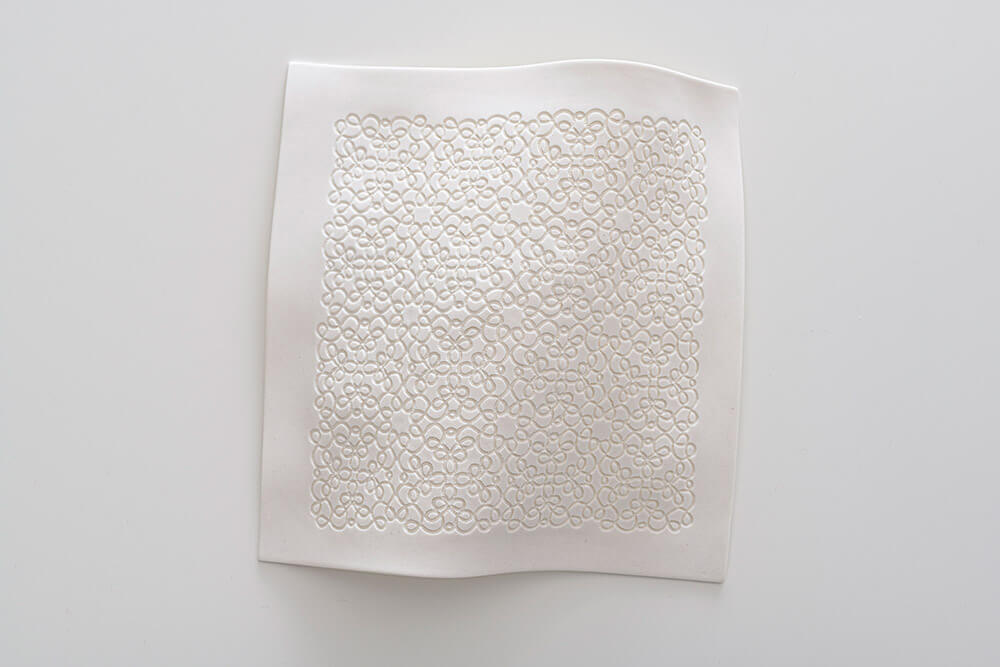

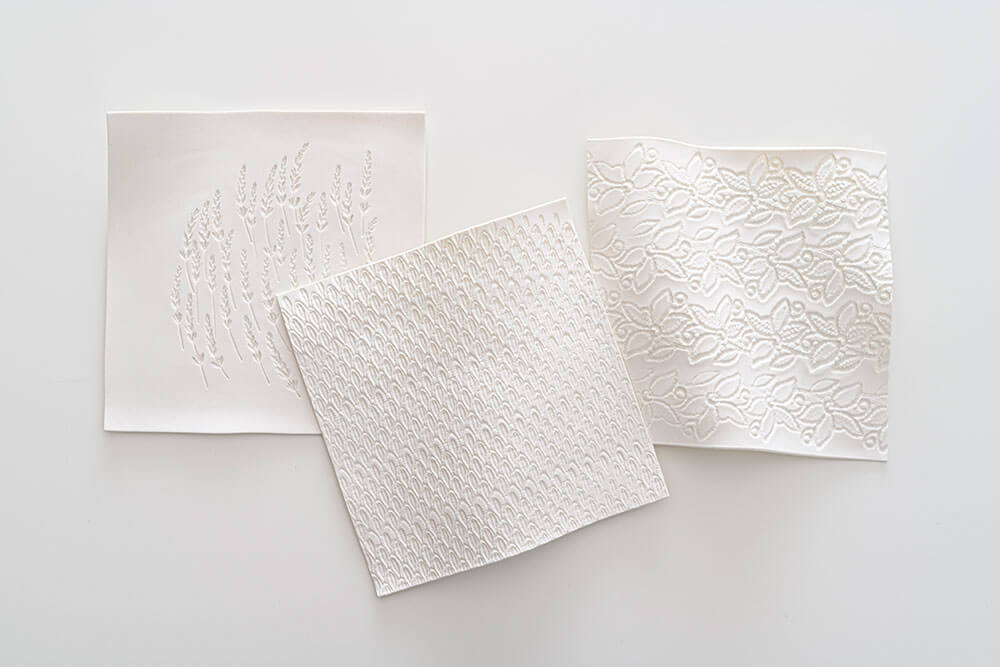

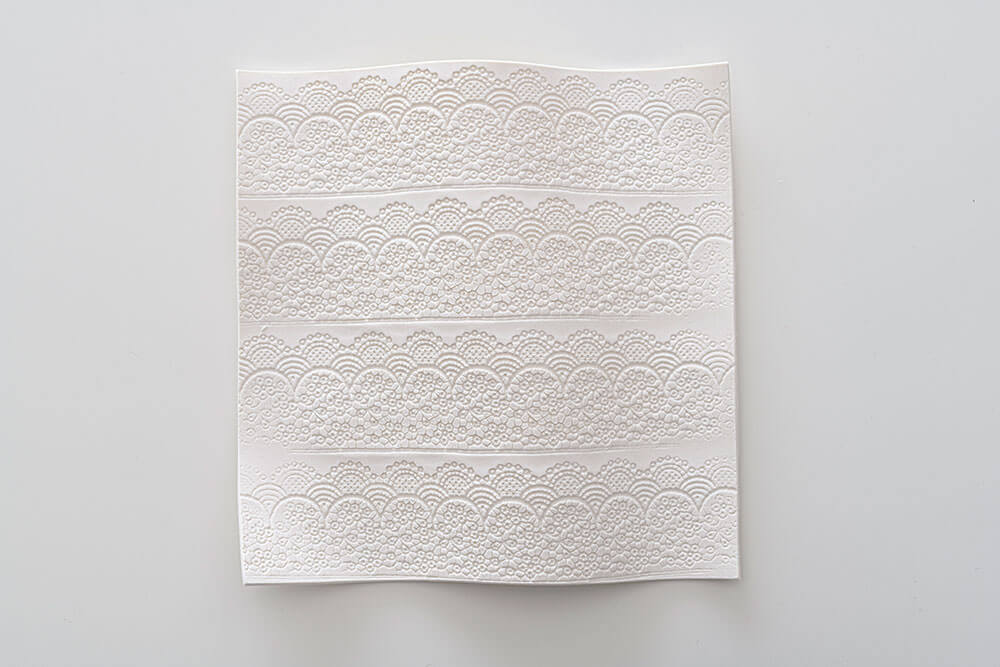

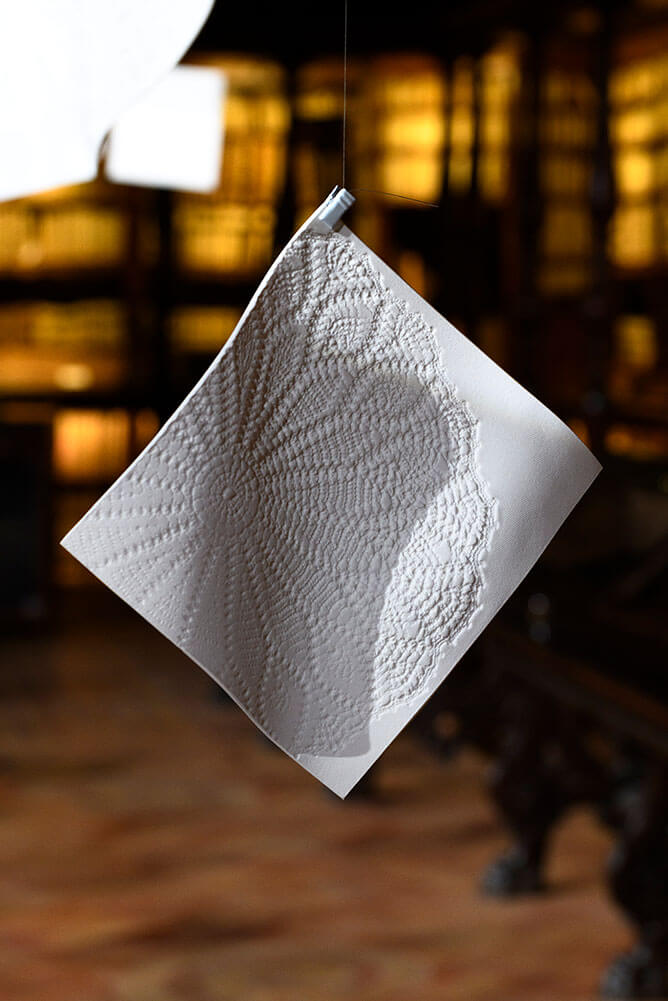

It would be a mistake to consider her porcelain handkerchiefs some kind of sophisticated synecdoche, each one is instead a powerful representation of wrong doings and we find each single life in the little red initials and the delicate variety of unique ornate lace. Mastria juxtaposes grace to a delicate stance that induces her to the difficult comparison and relation between creating matter that recounts a story for each woman. A clear and tragic story contrasting with the dark and opaque Othello, called sooty by Shakespeare himself referring to his soul not his skin colour.

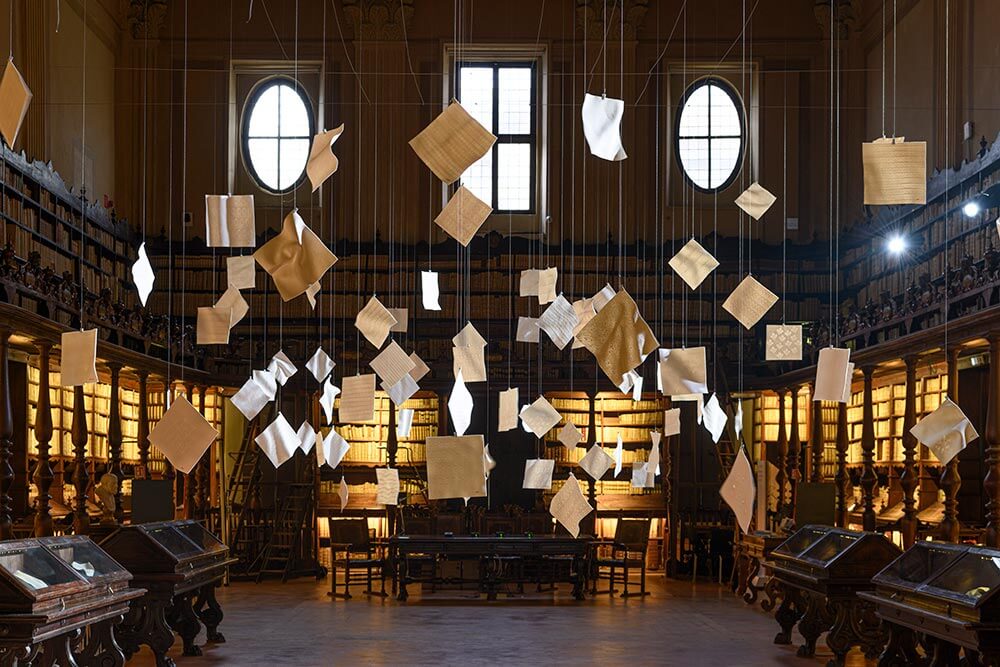

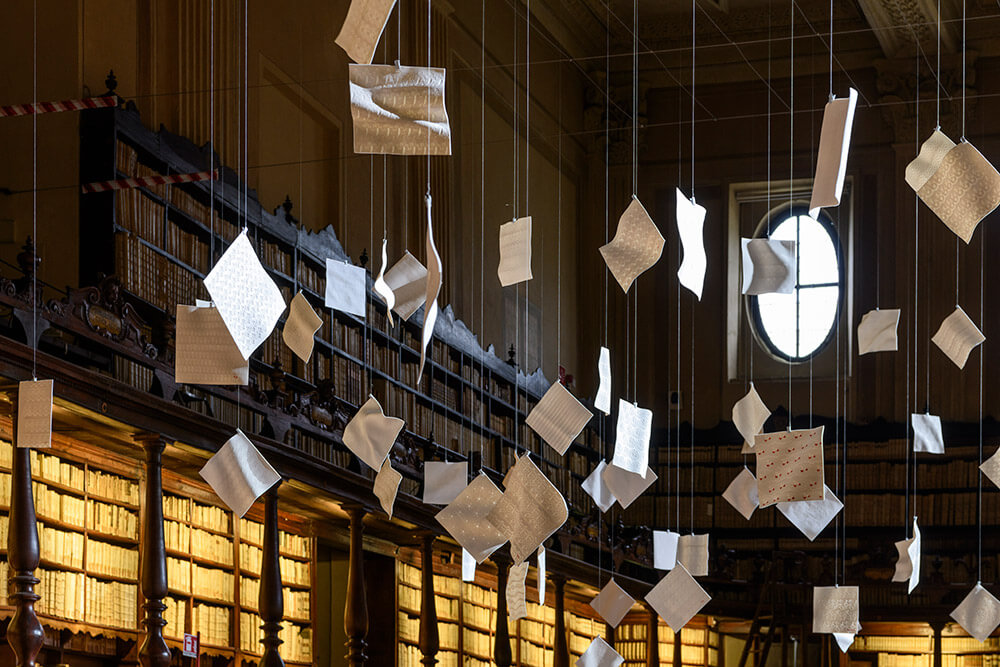

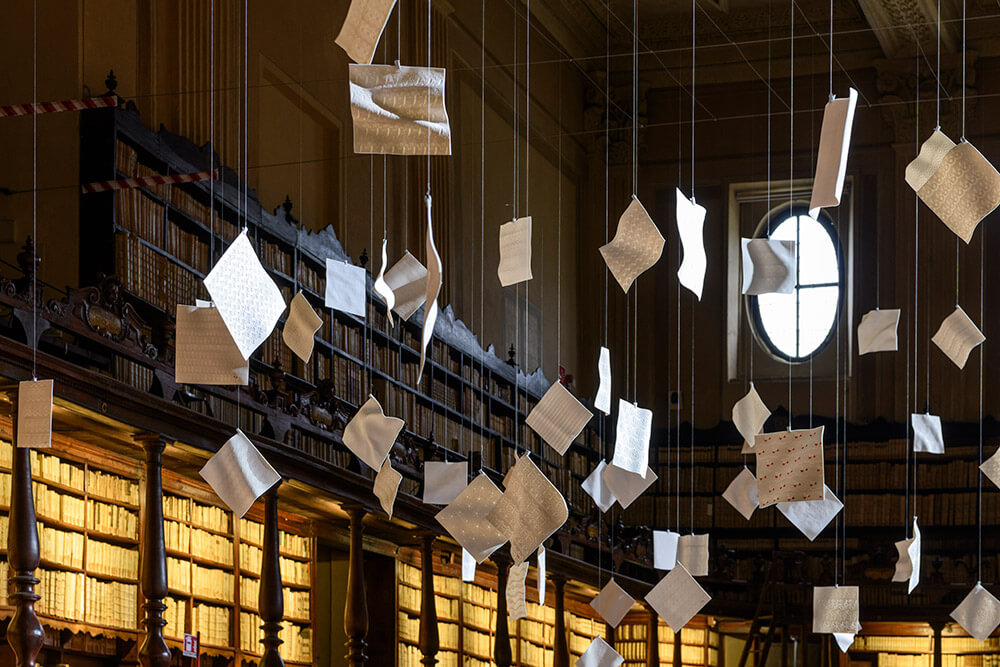

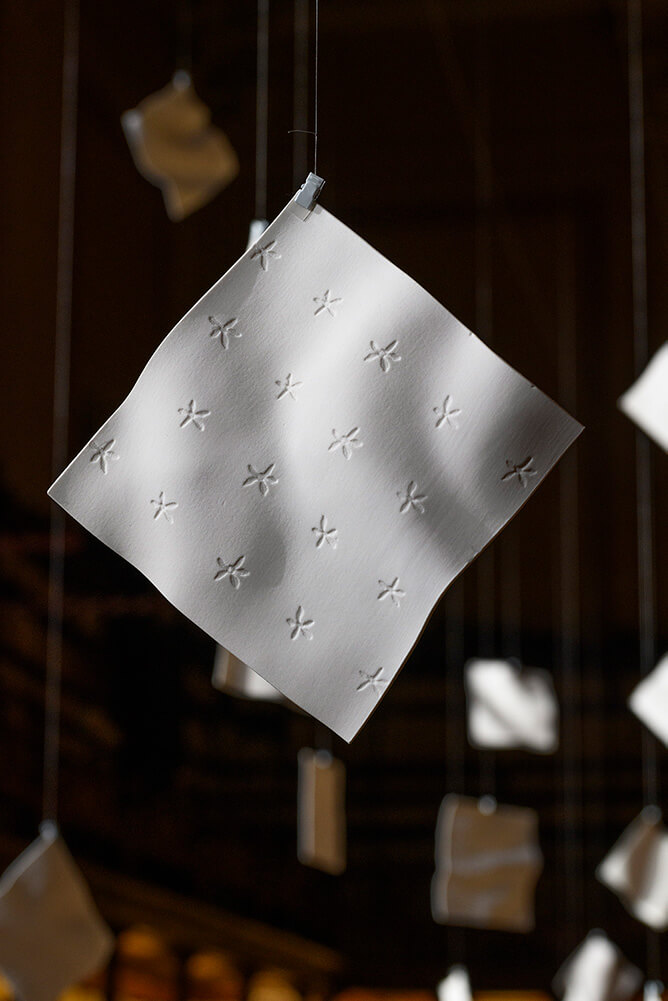

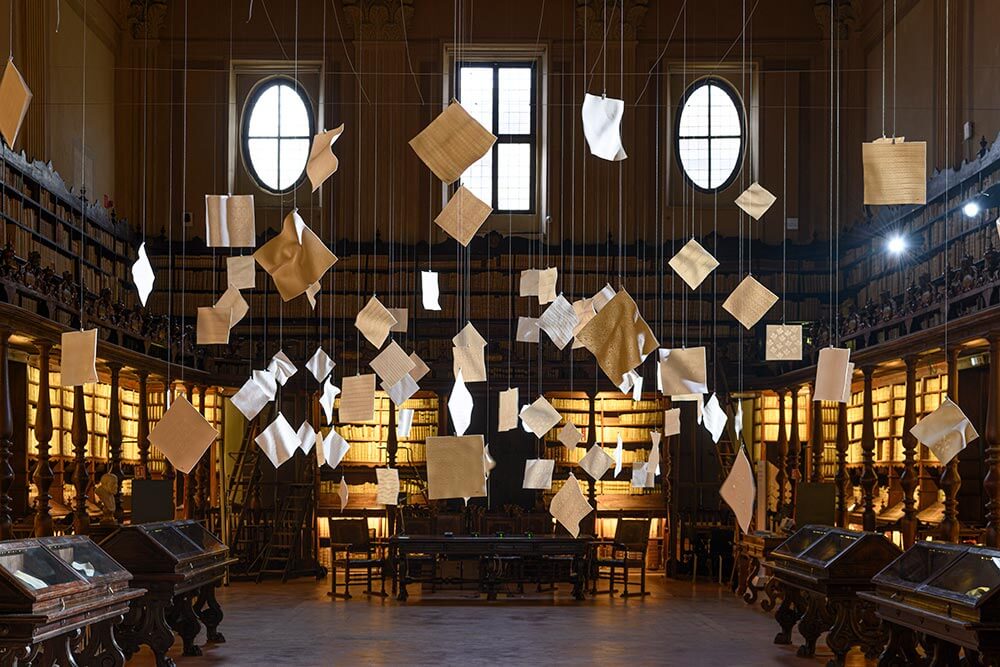

Not one of those white translucent handkerchief is a fragment. All together are a powerful coral narrative, each piece is a text written by the artist exactly inside the transparency of each handkerchief, allowing us to see a watermark, the paper element that identifies the privileged space for stories.

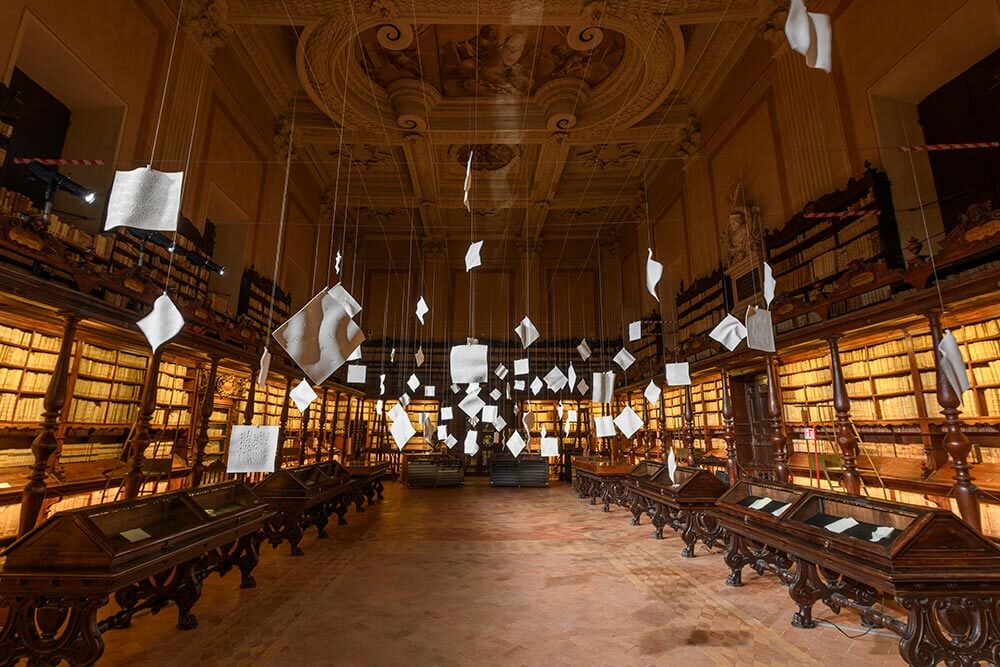

This is how the artist narrates the unspeakable without letting us retract our gaze, actually bringing us to establish an intimate relationship that becomes the real, where those who observe, maybe tangibly, recognize the one who has been cancelled.

The intimacy created by the fluctuating handkerchiefs is a sort of restraint that we could define benjaminian because it becomes palpable only with its apparent distance from the brutality of the act that it represents.

The distance creates the need to understand, creates the possibility to access pain, allows us to rebuild inside ourselves this particular intimacy and the rightful relationship between its diaphanous beauty, enchanted and conscious demureness born through the understanding that we all are in mourning.

Michela Becchis

Il fazzoletto di Desdemona